What is it I’m doing again?

or

How I Think Publishing Works

by Bethany Maines

As the author in residence to my friend’s and family, I frequently receive questions about the publishing industry. Well, let’s be honest, frequently is stretching it. More like occasionally, but I still get them and usually it goes something like this…

Them: You published a book? That’s cool. How does that work?

Me: Well, you write a book, try to get an agent, and then the agent sells it to a publisher.

Them: Yeah, but after that, how does it all work? And what’s this thing with Amazon that I’ve been reading about lately?

Me: Uh… Does any body need more salsa? I have to go get more salsa.

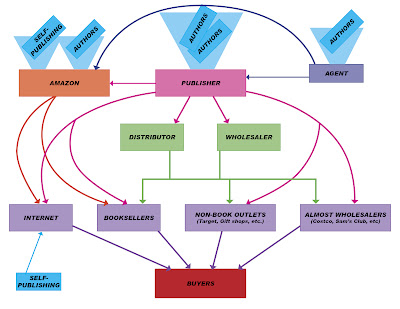

After awhile I just couldn’t eat anymore salsa, so I did some research and I thought some of you might be interested in what I found out. This, in broad strokes, as far as I can tell, is how books get to you. Don’t worry, I’ve also included a handy infographic. If you feel that I am incorrect in some way, please comment and let me know. This information is relatively hard to get in a linear progression, so I’ve had to piece it together as I come across it – I welcome all input.

Agents select manuscripts and sell them to publishers. At the same time Publishers also seek out manuscripts on their own – either from celebrities or from their “slush pile.” A manuscript gets selected to become a published book. The publisher has a couple of options for distribution; either they have sales reps who sell the book directly to booksellers and club stores (like Cost-Co and Sam’s Club) or they sell their books to distributors and wholesalers. Distributors and wholesalers sell books to bookstores, club stores, and they also sell to the non-bookstores like Fred Meyer, Target, gift shops, airports, and grocery stores. Publishers set the release date and release e-books at the same time that a distributor sends books to bookstores. Bookstores buy books at a 40-50% discount and sometimes have as much as 6 months to return books (if they don’t sell) to the publisher or distributor/wholesaler for either cash or credit against future purchases. Which is how an author’s sales can look great the first week after publication, but not so great months later after “the returns” are in. Publishers and booksellers also provide an internet location to buy the book. Then you, the reader, buy the book and/or e-book.

Now we get to Amazon. Amazon decided that it did not need wholesalers and most distributors… because they didn’t. They get their books directly from publishers or from distributors that represent publishing houses that don’t handle their own sales. Wholesalers and distributors are mad at Amazon because Amazon has essentially cut them out of the business. Bookstores are mad at Amazon because they feel that Amazon, due their deals with the publishers, can undercut bookstore prices, thus driving them out of business. Amazon has also offered a service to writers that let them self-publish (also known as vanity publishing) print-on-demand books and e-books; writers, of course, took to the process like a duck to water. With that much content floating around, next Amazon decided that it doesn’t need publisher’s either, because they can buy their own manuscripts and sell them. So… publishers, distributors, wholesalers, and bookstores are all mad at Amazon. So far the only people who aren’t mad are the consumers and the content providers – readers and writers.

Interestingly, I looked at the prices for print-on-demand books through Amazon a year or so back and I remember the number as being about $9 a book. Which, I thought, was a little high, but manageable if you were selling the book at $15. I recently looked at Amazon’s print-on-demand options and saw that they had raised the prices significantly and added additional fees for “expanded distribution.” Which leads me to speculate that Amazon may be attempting to let the air out of the self-publishing balloon. After all, why would they let self-publishers provide cheaper (and possibly just as good) content on Amazon distribution channels when it would be a direct competition to their own publications?

Nope, I think that just about sums it up! Well, at least for today, with the ever changing way publishing works, you might need a new info graph by tomorrow, but I thought you said it well in a nutshell!!

And at least your family asks realistic questions. I once had a relative who knew I'd "written a book." She picked up the ms, which was lying on a table. After flipping through, eventually she looked at me, and said, "Where's the cover? I don't get why there's no cover, that's not the way you get a book in a store." There ain't enough salsa in the world for that!

Don't forget the question that we all get asked repeatedly as well: If you're such a successful author, why do you still have a job?

Things are the same on the textbook side of things, where I toil by day. Like I said a few weeks back, I long for the days of the three-martini lunch and working on a Wang.

Great post, Bethany. Maggie

Yes, only I think e-publishing is changing everything, kind of tipping the publishing world.

Why do we do it?

Marilyn

I think your POD number is a bit high. POD is certainly more expensive on a per-book basis than offset printing is, but for the small publisher (self or otherwise), it's a viable option because the cost of entry is so low and there are no associated costs of warehousing.

My small press has two trade paperbacks on the market, and the unit cost is less than $4.75 for each. Once trade discounts are applied, there's still not much money left, but I also don't have high overhead or a staff to pay.

And, frankly, given that my e-sales now outpace paper by a 2-to-1 margin, the economics of print are starting to take on less and less importance.

That's great to hear Craig. After my research I formed the opinion that a per unit cost of $6 or less is what you'd have to be at to make self-publishing work in a traditional bookstore setting – I'm glad to hear it exists somewhere out there. To be clear I ONLY looked at Amazon and what they were charging writers. I just thought it was really interesting that their prices have jumped and that they are now charging additional fees for access to their "distribution channels," something that had previously been included in the price.

Great post. I think you are right about Amazon letting the air out of the self-pubbing balloon. Not only have they raised the prices on POD, but they have created a new feature on the e-books – REPORT TYPO. If a reader reports a typo, the price of the book can be refunded to the reader and the book can get pulled from the e-shelves until the typo is fixed to Amazon's satisfaction. With their new imprints hitting the physical and virtual shelves, it is not suprirsing that Amazon might want to weed out the competition a bit. It is interesting times….

But are self-publishers really competition in the sense that we understand the word? I don't think so.

To get my books into bookstores, which is still important to me, I have to put a 55 percent trade discount on them (which amounts to 35 to 40 percent for the retailer). Amazon, as a seller of my books, gets in on that action, too. If Amazon is getting 35 percent, I'm not a competitor; I'm a source of revenue.

Same thing with the e-books. Even at the 70 percent royalty rate, Amazon is getting 30 percent for doing no more than storing a book on a server.

I interpret the assault on typos as a retailer telling its suppliers that it demands a certain level of quality. I don't think that's an altogether bad thing.

Well, the number one comment I've heard from bookstore owners I've talked to is that they are looking for an assurance of quality that they can't always get from self-publishers (all writer's think their book is grrrrrEAT!). I think we can all agree that better quality writing is always… better. Amazon is using writers as a revenue stream, so the concept of "competition" is exactly direct, but I can't think that Amazon's costs have increased in the print on demand department. So what's causing the rise in price?

You're absolutely correct about what bookstore owners want. That's why I'd have never started a publishing business (note: I publish other writers in addition to my own projects) without first developing a relationship with booksellers. Their confidence in a book is absolutely essential to its being stocked and, even more important, recommended to their readers.

It looks to me that CreateSpace has created a per-book surcharge to get it into "expanded" distribution channels. All the more reason to go with an outfit like Lightning Source (owned by Ingram Content Group), which has slightly higher upfront costs to get a book into production but doesn't take a chunk over and over again.