Taking Editorial Feedback Professionally

by Linda Rodriguez

At the end of a course I recently taught, one of my students

sent me a scene-by-scene outline of her book. I could see as I considered it

where her problem lay—and it was a pretty major problem. I had to consider

whether to soft-pedal my response. This student had been very open about how

discouraged she was, and I certainly didn’t want to discourage her any more

than she already was. Still, I gave her my best detailed critique of what her

book’s problems were and what she could do about them. Then, I took a deep

breath and tried not to think about it.

sent me a scene-by-scene outline of her book. I could see as I considered it

where her problem lay—and it was a pretty major problem. I had to consider

whether to soft-pedal my response. This student had been very open about how

discouraged she was, and I certainly didn’t want to discourage her any more

than she already was. Still, I gave her my best detailed critique of what her

book’s problems were and what she could do about them. Then, I took a deep

breath and tried not to think about it.

I stopped doing developmental editing for quite a while

after a run of several clients who didn’t really want truthful, constructive

criticism, even though they were paying for it. When I did return to

developmental editing (at the request of a couple of students), I wrote a

one-page information sheet that I give to all prospective clients. It explains

what developmental editing is, what it is not, discusses the cost and details

of what it entails, and ends with this paragraph.

after a run of several clients who didn’t really want truthful, constructive

criticism, even though they were paying for it. When I did return to

developmental editing (at the request of a couple of students), I wrote a

one-page information sheet that I give to all prospective clients. It explains

what developmental editing is, what it is not, discusses the cost and details

of what it entails, and ends with this paragraph.

“This kind of editing entails clarity and honesty about the

manuscript’s strengths and weaknesses and how to improve it, always keeping in

mind the writer’s original vision. It is not for writers who have problems with

criticism of their work or who are seeking an ego boost. For such writers,

developmental editing is a waste of their money and of my time.”

manuscript’s strengths and weaknesses and how to improve it, always keeping in

mind the writer’s original vision. It is not for writers who have problems with

criticism of their work or who are seeking an ego boost. For such writers,

developmental editing is a waste of their money and of my time.”

One of my current clients laughed when she read it and said,

“It sounds like you’re trying to drive away business, not attract it.”

“It sounds like you’re trying to drive away business, not attract it.”

I nodded. “I am. If someone’s not serious and professional,

I don’t want to deal with them.”

I don’t want to deal with them.”

My recent student came through like a champ, though. She

emailed a long thank-you for the critique, saying no one could or would ever

tell her what wasn’t working in her book. She’s now all enthusiastic about

doing the necessary work to make her book good. And I was grateful and relieved

to read that she has such a professional attitude.

emailed a long thank-you for the critique, saying no one could or would ever

tell her what wasn’t working in her book. She’s now all enthusiastic about

doing the necessary work to make her book good. And I was grateful and relieved

to read that she has such a professional attitude.

Aspiring writers sometimes forget that, even when they have

publishing contracts, they will have editors who will point out ways in which

their books could be stronger. If they’re lucky, their agents will already have

done some of that. It’s a natural part of the publishing process. Almost every

change my editor ever wanted me to make worked to create a better, more

powerful book. Part of being a professional writer is being able to make good

use of professional editing critiques from teachers, developmental editors, agents,

and publishing house editors.

publishing contracts, they will have editors who will point out ways in which

their books could be stronger. If they’re lucky, their agents will already have

done some of that. It’s a natural part of the publishing process. Almost every

change my editor ever wanted me to make worked to create a better, more

powerful book. Part of being a professional writer is being able to make good

use of professional editing critiques from teachers, developmental editors, agents,

and publishing house editors.

What are your feelings about editorial feedback? Are you one

of those writers who see the editor as a natural enemy? Or are you one, like

me, who sees the editor as the person who’s trying to keep you from looking bad

in public?

of those writers who see the editor as a natural enemy? Or are you one, like

me, who sees the editor as the person who’s trying to keep you from looking bad

in public?

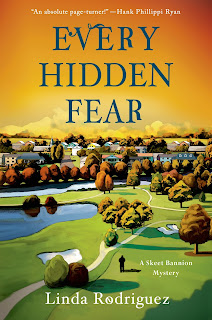

Linda Rodriguez’s three novels published by St. Martin’s

Press featuring Cherokee campus police chief, Skeet Bannion—Every Hidden Fear, Every Broken Trust, and Every

Last Secret—have received critical recognition and awards, such as Latina

Book Club Best Book of 2014, the Malice Domestic Best First Traditional Mystery

Novel Award, selections of Las Comadres National Latino Book Club, 2nd

Place in the International Latino Book Awards, finalist for the Premio Aztlán

Award, 2014 ArtsKC Fund Inspiration Award, and Barnes & Noble mystery pick.

Her short story, “The Good Neighbor,” published in the anthology, Kansas City Noir, has been optioned for

film.

Press featuring Cherokee campus police chief, Skeet Bannion—Every Hidden Fear, Every Broken Trust, and Every

Last Secret—have received critical recognition and awards, such as Latina

Book Club Best Book of 2014, the Malice Domestic Best First Traditional Mystery

Novel Award, selections of Las Comadres National Latino Book Club, 2nd

Place in the International Latino Book Awards, finalist for the Premio Aztlán

Award, 2014 ArtsKC Fund Inspiration Award, and Barnes & Noble mystery pick.

Her short story, “The Good Neighbor,” published in the anthology, Kansas City Noir, has been optioned for

film.

For her books of poetry, Skin

Hunger (Scapegoat Press) and Heart’s

Migration (Tia Chucha Press), Rodriguez received numerous awards and

fellowships. Rodriguez is 2015 chair of the AWP Indigenous/Aboriginal American

Writer’s Caucus, past president of the Border Crimes chapter of Sisters in

Crime, a founding board member of Latino Writers Collective and The Writers

Place, and a member of International Thriller Writers, Wordcraft Circle of

Native American Writers and Storytellers, and Kansas City Cherokee Community. Find

her at http://lindarodriguezwrites.blogspot.com.

Hunger (Scapegoat Press) and Heart’s

Migration (Tia Chucha Press), Rodriguez received numerous awards and

fellowships. Rodriguez is 2015 chair of the AWP Indigenous/Aboriginal American

Writer’s Caucus, past president of the Border Crimes chapter of Sisters in

Crime, a founding board member of Latino Writers Collective and The Writers

Place, and a member of International Thriller Writers, Wordcraft Circle of

Native American Writers and Storytellers, and Kansas City Cherokee Community. Find

her at http://lindarodriguezwrites.blogspot.com.

Excellent post, shall share. Stephen King said it best: Kill your darlings. But, as you say, not everyone is ready to do that. Kudos to your student!

Judy, Stephen King's book is one of the must-read books on a list I give my students. It's always a huge step toward professionalism when an aspiring writer learns to look objectively at editorial feedback and ask, "Is this good for the book?" without worrying about personal vanity.

Down deep, underneath our rational selves, I suspect most of us are hoping emotionally to have feedback that says something like this…YOU have written the best thing ever since War & Peace. YES, YOU are right up there with Tolstoy! But that ain't gonna happen, and we need to cope with it and love the criticism that we begged/paid for. I was in a book club for 15 years and listened as 12 people never agreed on which was a great book to read. If even Pulitzer Prize winners were trashed by some, then who was I to think that EVERYONE would adore my little mystery? This experience helped me be realistic.

GREAT POST, Linda, and a very, very necessary one too!

Thanks, Kay! I think you're so right. It's human nature to want to hear only praise, but we grow as writers when we move beyond that.

Excellent post, Linda. Thank you for sharing.

Thank you for stopping by and commenting, SKM.

I just received a detailed seven page critique of the first 25 pages of my book. Everything the editor said was necessary and correct, big fundamental problems and smaller, easier fixes. I get it and I'm doing it.

Margaret, having had you as a student, I'm not surprised at your professional attitude. It's not as common as you might expect among aspiring writers, but they'll never move out of the aspiring category if that doesn't change

Same with a critique group–everyone needs to able to take criticism and help without being defensive.

You're right, Marilyn. They could look upon it as practice for when they receive their first professional edits.

I'm in your camp. When I provide editorial or developmental feedback, it's for one purpose only: to help the author make her book the best it can be. When I put my own work out for critique or editing, I demand the same. I don't want to look like an amateur, and I can pretty easily separate myself from my work. I tell them to give it to me straight and don't try to spare my feelings. It's just much better and cleaner that way.

That's it exactly. Those who have problems with this are unable to separate themselves from their work. Something all writers must learn to do.

As far as editing other's stories, it's always easier to work with authors, or aspiring authors, who know an editors job is to make the project the best it can be. Protecting egos from hurt feeling can zap energy. Even when an editor offers improvements with respect, support, and encouragement, egos can be bruised. But those who allow their work to be edited by others must remember: it’s their story, and the author has the right to decide the best way to tell it. At the same time, it’s important to listen to those who have more experience—especially if the author wants to improve his/her craft.