Figures of Speech

Figures of Speech

by Saralyn Richard

An English major in college, I was required to take courses in Chaucer/medieval lit, Shakespeare, Milton, 18th and 19th century literature, and American literature, among others. Of these, the dreaded subject was Milton, mainly because the brilliant poet and author of Paradise Lost took full advantage of the vast body of history, philosophy, religion, politics, and literary criticism of the day, and analyzing and interpreting even a few lines of his work could send a person down a rabbit hole for eons.

I had read excerpts from Milton’s works in high school, and I’d found them dry and uninteresting, but when I arrived in my Milton class junior year in college, I had a whole different experience. Call it an awakening, a challenge, a puzzle—whatever—I delighted in the intrigue and purpose of Milton’s language, and I couldn’t get enough.

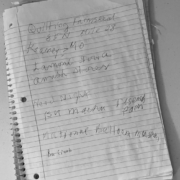

After the semester, I decided to continue studying Milton by undertaking two semesters of work, researching and writing an honor’s thesis. My focus of study was figures of speech.

Most people understand the function of figurative language and can identify and explain similes, metaphors, personifications, and analogies. Few, however, realize that these represented only a miniscule number of the figures of speech available for Milton and other writers of the Elizabethan and Puritan eras.

I could write treatises—or an honors thesis—about what I learned from books, such as George Puttenham’s The Arte of English Poesie, or Henry Peacham’s The Compleat Gentleman, but for this blogpost, I’ll say that I was astounded by the more than 456 figures of speech used by Renaissance writers of poetry and prose.

The literary devices included repetitions, inversions, comparisons, and rhetorical devices to tickle the ear and tempt the mind. Some of the more obscure, but popular, figures of speech were anastrophe, litotes, and anadiplosis.

Once I learned about them, I had fun hunting for them in Milton’s verse. Each find unlocked a bit of the magic that made Milton’s writing so memorable.

Fast forward to the 21st century, and I was teaching creative writing to students aged 55 and older at the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute. I introduced a unit in figures of speech, and we dug into definitions and examples of a variety of the lesser-used devices. I challenged learners to use some, like synecdoche and metonymy in their writing, and the results were amazing.

Also, when I read a work of fiction by an author like Poe, Tartt, Kingsolver, or Irving, and I find a turn of phrase that is particularly appealing, I love to deconstruct the language. Do you do the same? What is your favorite figure of speech, and which author do you think is especially adept at using figurative language?

Saralyn Richard writes award-winning humor- and romance-tinged mysteries that pull back the curtain on people in settings as diverse as elite country manor houses and disadvantaged urban high schools. Her works include the Detective Parrott mystery series, two standalone mysteries, a children’s book, and various short stories published in anthologies. She also edited the nonfiction book, Burn Survivors. An active member of International Thriller Writers and Mystery Writers of America, Saralyn teaches creative writing and literature. Her favorite thing about being an author is interacting with readers like you. If you would like to subscribe to Saralyn’s monthly newsletter and receive information, giveaways, opportunities, surveys, freebies, and more, sign up at https://saralynrichard.com.

Saralyn, I’ll wager you are a fabulous instructor. Like you, I was required to read the classics in high school and found them dry. Unlike you, I didn’t pursue them later. I did study Poe in college. Later, I became enthralled by Charles Dickens, Taylor Caldwell, Daphne du Maurier, Barbara Erskine, Alexander Dumas to name a few. I devoured mysteries of course. Lawrence Sanders comes to mind. When reading, I often stop to examine a turn of phase or an author’s voice, and I always stop at an unknown or peculiar word in its usage. It’s one of the great joys of reading.

Thanks for the comments, Donnell. Your list of favorite authors is impressive, too, and I’ll bet you learned a lot from their uses of figurative language. You’re right about the joy of reading, too, and I would add the joy of writing!

Absolutely! The joy of writing as well.

Saralyn, you had me reaching for the dictionary. I’d never heard of some of the terms you used, but once I read the definitions, I realized I was quite familiar with all of them. However, I have to admit, I’m quite partial to puns.

Smiling at the image of you, looking up the words in the dictionary. That’s part of the fun of figurative language–playing with words. (And I love puns, too.)

I am a peasant when it comes to reading despite having been an English major. I read for the lyrical sound of the words and their flow. Although I recognize good writing and the use of phrasing and language devices, I ignore them to simply read for joy.

I’ll bet what you do is suppress, rather than ignore. And that’s perfectly fine. The important thing is that the words have their intended effect on you.

This is all way above my paygrade, but in a much simpler way I love a writer who can use a word in a new way. A way that pushes the envelope for that word’s definition. When that happens it’s like a tickle in my ear, and I don’t even mind that for just a moment I’m pulled out of the story.

That’s exactly how I read, only I’m not really pulled out of the story. The story is somehow amplified for me by the figurative language.

Professor Saralyn, I looked up anastrophe, and what did I find? Like our venerable Edgar Allen Poe, the beloved Yoda (of Star Wars fame) is also a master of anastrophe, as in the line, “The greatest teacher, failure is.” I feel smarter already. Thanks!

I’m sure the T.U. English Department would be proud of you–and perhaps of me, as well. Lifelong learners we both are.

I would love to take one of your classes.

That would be a blast, wouldn’t it?