Sometimes you meet an author that just makes you scratch your head and go, “Huh. Glad she thinks she’s all that, because her attitude and people skills sure leave a lot to be desired.”

Then you meet an author who is the complete opposite. She’s friendly, gracious, enthusiastic, approachable, and seems to *get* that writing books, like so many other things, is about building relationships.

Okay, here’s the story. I run Books on the House, as many of you know. The site is going amazingly well. 10,000+ total visitors per week. 24,000+ total page views per week. Fantastic authors have signed on to be featured and to promote their books. These include the phenomenal Sarah Addison Allen, Lori Wilde, Ridley Pearson (who often writes with Dave Barry), Allison Brennan, our own Susan McBride, Jane Yolen (children’s book superstar), and so many more. They come on, their books are featured, they are featured, and at the end of the week, they give away a few copies of their book to the lucky winners for the week (all randomly chosen). Readers find new-to-them authors and books. Authors find potential new readership. Exposure is huge. It’s win-win.

Well, a while back, I happened to be talking with a writer who happens to share my agent. I’ll call her Writer A. I mentioned to Writer A that she should think about coming on Books on the House. I’d do a big splash for her and give her some upgrades (camaraderie and all that, right? Same agent! Mutual friend! Just reaching out to her…).

Her response was immediate and so dismissive that I was honestly stunned. She said, curtly, I might add, “Thanks, but no thanks.” She’s made it a policy, she said, to never, ever give away free books.

This shocked me on a couple of levels. First, whether you’re a debut author or a multiple bestseller, I just think it’s a good idea to be friendly to other people. Life is all about building relationships. Without the people around us, the things in our life and what we go through cease to have meaning.

Being nice = good karma.

I didn’t care if this author came on Books on the House. I was simply offering her the opportunity, along with some freebies, because of our shared agent and a mutual friend. I know how hard it is to let readers know about your book which is why I created the site. I thought she might like exposure for her debut novel. She could have politely declined. Like I said, I didn’t care if she came on, I was just reaching out.

She could have handled it more professionally. She didn’t, and that rubbed me wrong.

The other issue I had with her response was her ‘policy’ to never give away a free book. SHOCKING!!! This business, now more than ever, is built on word of mouth. Authors receive FREE COPIES of their books for just this purpose. We should be giving them away to the press, to reviewers, and to avid readers in our target audience who will then spread the word. Again, good karma. This author’s philosophy is so vastly different from mine, I wanted to get other opinions. Your opinions Maybe I’m WAY off the mark.

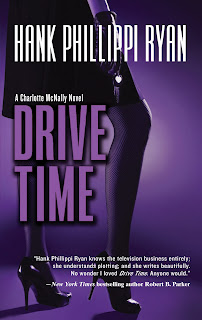

I don’t think so, though. I come now to example 2. Hank Phillippi Ryan. Now, I admit, I haven’t read Hank’s books yet. I’ve had them on my ‘to buy’ list, but, shoot, there are, like 500 books on that list, and I don’t own a digital reading device yet, btw, so 500 books would take up WAY too much space.

But I digress.

Hank is on Books on the House right now. Her fourth book, Drive Time, just came out. When she contacted me, she was super enthusiastic, not about coming on my site to promote, but just about her books, about people discovering her books, and about making connections with readers. We talked on the phone and I liked her right off. She has that infectious personality that just makes you want to smile and spend time with her. I wish I could go visit Boston just to drop in on Hank!

Anyway, we worked together to come up with something different to really get people to interact on the site this week and boy has it been successful. First, we did a Skype interview (which is where I also discovered I REALLY respect Hank Phillippi Ryan). She’s smart, successful, driven, accomplished, caring, empathetic… I could go on, but I’ll leave you to watch the interview yourselves (Interview with Hank Phillippi Ryan Part 1 and Interview with Hank Phillippi Ryan Part 2). Did I mention she’s won, like, a boatload of Emmies for her investigative reporting? Warrior woman. I like it.

Hank wanted to do something fun for readers and to give many people the opportunity to win copies of her books. It wasn’t just about getting people to buy Drive Time. (On a side note, I’ve seen authors practically begging people to buy their books so they can keep writing. I cringe when I see this because, again, we have to build relationships FIRST and sell books SECOND.) Hank wants people to know about Charlotte McNally, her sleuth. She has something to say to her readers through her character and how better to introduce her character and books to people than by talking about them, loving them, and graciously giving away a few copies to avid readers? Actually, she’s giving away more than a few. One a day, plus a grand prize of the whole set. And she’s giving away a prize to commenters, something no one has done before on Books on the House. She’s interacting with the commenters, she’s talking to readers, and she’s building connections.

Her policy is to spread her books around, and I like that approach!

I tell you what, I was so enamored with Charlotte McNally (being of a certain age and trying to figure out what her future will be given her choice of career over romance) that I immediately went out and bought Prime Time, the first book Hank’s series.

Have I bought Writer A’s book? Nope. It sounds like it is a fun read, but I’ve not heard her talk about it, haven’t felt her love for her story or characters, and haven’t felt her love and respect for readers. All I’ve seen is her drive to sell books. Her ‘policy’ turned me off, quite frankly. She’s all about selling books, not building relationships.

Will I buy books from the other type of author I mentioned? Doubt it. I get that people want to write for a living. So do I. But when an author spends his or her time focusing on that, assuming that readers care whether or not he or she continues to write, I think they’re missing the point. How can they care when they’ve not read the author’s first book? And why will they read the first book if they know nothing about it, don’t feel his or her passion for the characters, their journey, or the themes he or she is compelled to write about? Again, all I’ve seen is a stifling drive to sell books, not build relationships with readers. I guess it can be a fine line, but it’s one I think authors need to be aware of.

I want to hear your thoughts. Should authors care more about building relationships with readers? As a reader, are you more drawn to an author who does this? As an author, how do you find balance between the drive to sell books and the desire to build relationships with readers?

Am I just plain loca?

Misa Ramirez/Melissa Bourbon