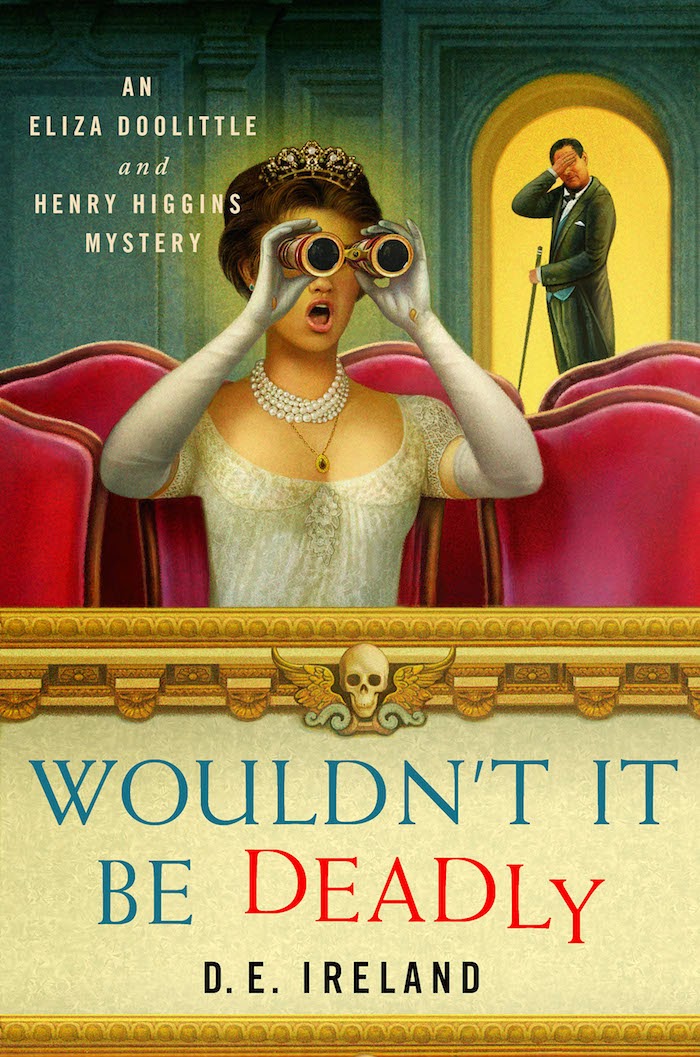

SLEUTHING WITHOUT A LICENSE – Guest D.E Ireland

Mystery readers have long been aware that some of the best

literary detectives are rank amateurs. Unlike private eyes, FBI agents, and

police officers, amateur sleuths must fit in crime solving along with their day

job. These part-time detectives not only break the rules, they’re often unaware

of what the rules are. Still, this doesn’t stop them from unearthing evidence,

tracking down leads, and nabbing the killer.

Of course, they do operate with a few drawbacks. For one

Of course, they do operate with a few drawbacks. For onething, most do not carry weapons. An amateur sleuth also can’t obtain a search

warrant or wire tap, which may lead them to breaking and entering – a crime. One

of the biggest risks of not being a professional is the possibility of arrest,

since law enforcement views an amateur with suspicion or irritation. If an

amateur does find evidence or clues, the resources of a forensics or crime lab

are not available. This is why so many cozy mysteries feature police officers

or FBI agents as continuing characters; these characters are often a family

member or a romantic interest of the protagonist.

intelligence, ingenuity, and intuition. And a private citizen interested in

solving crimes is not without resources. Scores of databases are available

online, such as tax assessor records, genealogical history, property records,

military service, etc. And if the sleuth knows the person’s social security

number, the prefix will tell them the state where the number was issued. County

records and newspaper archives also help flatten the playing field for the

non-professional detective. But the most valuable asset for an amateur is

gossip. Most people are wary or fearful of the police. If the person asking

questions is a friend who owns the local bakery, the answers may be more

forthcoming,

Cozy mysteries are frequently set in picturesque small towns,

Cozy mysteries are frequently set in picturesque small towns,and the amateur sleuth is usually a long-time resident. This allows them easy

access to all the juicy family secrets, and they know where all the bodies –

literally and figuratively – are buried. Such knowledge gives them an advantage

over an outside investigator. Detectives

in cozies often own businesses such as tea shops, B&Bs, bookstores, and

vineyards. This constant influx of customers and visitors provides an ever-changing

pool of suspects and victims. The reader is also showered with lots of

fascinating details about the protagonist’s business.

Popular small business

cozies include Laura Child’s Tea Shop Mysteries, JoAnna Carl’s Chocoholic

mysteries, and Susan Wittig Albert’s China Bayle’s Herb Shop series.

enforcement. More than one police department has called in a psychic to help

them unravel an especially difficult case. These are sleuths who possess a

unique skill set rarely found in a forensics lab or police station. Not

surprisingly, mystery series have sprung up which feature paranormal

investigators. These detectives include not only psychics, ghost hunters, and

witches, but also actual supernatural creatures such as vampires and

werewolves. Perhaps the most famous in this subgenre is Charlaine Harris’s

Sookie Stackhouse books.

past – when investigative methods were minor or nonexistent – might be easier

to write. Not so. Cozy historical authors setting their stories in London must

be aware of how British ‘Bobbies’ came into service, and that 1749 saw the founding of the Bow

Street Runners, the city’s first professional police force. In the American

colonies, law enforcement was the prerogative of constables, government

appointed sheriffs, and voluntary citizen “watches” who patrolled the town’s

streets at night. This leaves plenty of opportunity for amateur sleuths,

especially since the country’s first 24-hour police force did not appear until

1833 in Philadelphia. Books set during the early years of law enforcement

include the Bracebridge Mystery series by Margaret Miles, Maan Meyer’s Tonneman

books, and Patricia Wynn’s Blue Satan series set in Georgian London.

While there weren’t established police forces prior to the

19th century, there were lawyers. And it’s not only John Grisham and

Scott Turow who know that attorneys have access to both information and a wide

range of criminals. The practice of law has been a legalized profession since

the time of Roman Emperor Claudius in the first century. What a perfect

occupation for an amateur sleuth, as long as he doesn’t run afoul of the

ultimate arbiter of justice: the reigning monarch. And when the sleuth is the

monarch herself, as in the Queen Elizabeth I series by Karen Harper, then you

have the most powerful detective of them all.

with a budding police force. Ministers and officials could make things quite

dangerous for a sleuth, especially if that sleuth is an ordinary citizen

without wealth and powerful connections to back him up. And depending on the

time period, a wrongly accused victim did not have forensic science techniques

to help exonerate him. Fingerprinting wasn’t admissible in court until after

the turn of the 20th century, along with

photographs of the crime scene and victims. In both historical and contemporary

novels, amateur detectives have a hard time convincing police officials of

their theories. Even worse, the killer invariably targets the sleuth as their

next victim in order to avoid discovery.

murder investigation or else it wouldn’t make sense, given the inherent danger.

In our own debut mystery, Eliza Doolittle must prove that Henry Higgins is innocent

of murdering his chief rival; it is her friendship and loyalty to him that

spurs Eliza on. In Cleo Coyle’s first Coffeehouse mystery, the police believe

an attack on Clare’s employee was accidental; Clare believes otherwise and adds

‘amateur sleuth’ to her resume. And in Barbara Ross’s Maine Clambake series,

amateur sleuth Julia must rescue her family business while solving a murder on

its remote island premises.

to chase after criminals. Luckily, they seem to be quite good at it.

Leave a comment to get your name in the drawing for a hard copy of Wouldn’t It Be Deadly.

D.E. Ireland is a team of award-winning

authors, Meg Mims and Sharon Pisacreta. Long time friends, they decided to

collaborate on this unique series based on George Bernard Shaw’s wonderfully

witty play, Pygmalion, and flesh out their own

version of events post-Pygmalion.