What to Remember—T. K. Thorne

Writer, humanist,

dog-mom, horse servant and cat-slave,

Lover of solitude

and the company of good friends,

New places, new ideas

and old wisdom.

Holocaust Remembrance Day was a month ago. But it has so many echoes to the current day, I am still thinking about it.

There is so much to remember, but I am plagued by two questions at the moment. How do people believe things? Why do they believe things?

Let’s start here:

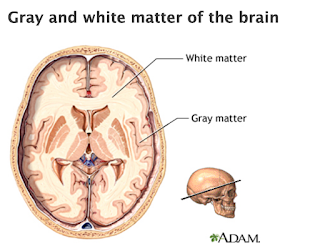

We are humans. We are emotional beings. Our brains evolved in stages. Scientists tell us that the part our cognitive structure that makes us thinking beings (i.e. organisms that can project possible futures and plan for them) formed literally on top of the reptilian brain, which was responsible for flight/flight reactions and keeping us alive in a threatening world. We still have that reptilian part of our brains; it is part of us, and it is often in conflict with the “thinking” part of our brain.

But our amazing mind/body has adapted a strategy to integrate both brains and all the different parts of our brains. It does this with the bridge of STORY.

Story is the structure by which we not only integrate the various parts of ourselves (different parts of our brain) but also our place in the world. It is how we know we “are,” as opposed to everything we are not. “I” has boundaries that end with my skin. I am not the chairs I sit on, the air I breathe, the other people in my social orbit. But my story about myself allows me to include other things and people as connected to me. This is my chair; my house; my family. I “am” angry; I “am” sad.

These things and relationships are not real. They are stories.

Images that fall on our retinas at the back of our eyes are upside down. Our brain rewrites the story of what we are seeing by flipping the image over for us and telling us that is what we see. Have you ever looked at something or a picture of something and it took several moments to figure out what it was? You are “seeing” without the brain’s interpretation (story) about what you are seeing.

Ultimately, everything is connected to everything. We are all bits of energy dancing in a temporary form. It is story that gives everything context.

In earlier times, probably before the sophistication of language, we may very well have communicated through body movements and dance, perhaps accompanied by sounds mimicking animals. Perhaps hunters acted out how to spot and stalk and kill prey. Perhaps they figured out a way to explain where a crop of berries grew (as bees dance to give the location of flowers.). We still see these types of communication in Native American dancing. This was rudimentary storytelling. Its usefulness in survival is obvious.

Many psychologists have pointed out the powerful influence of “the story we tell ourselves about ourselves.”

“I am a victim of abuse vs I am a survivor of abuse vs I am an overcomer of abuse.” How we tell our stories matters.

But the point I want to make here is that our brains are designed to interpret via story. If we are told something when we are young, it can become subconsciously incorporated into our perceptions, our story about ourselves. Even as adults, we susceptible to stories, especially if they are ones we are primed to believe.

Here’s another important fact. Science is indicating that there are literally different portions of our brains that “speak up” at different moments and that one of the functions of our consciousness is to determine which one to “listen” to. Have you ever had conflicting voices in your mind? That chocolate looks so good! At the same time a different voice says, It is not healthy; don’t do it! Ultimately, you have to decide which story to believe in.

Science says we are more likely to believe bad news than good, which makes sense. It is more important to pay attention to the information that a tiger is prowling close than that nothing has been spotted in the tree canopy. Thus, the story that other types of people are dangerous or threats to us finds easy access in our brains.

We also pay more attention to information that aligns with what we already believe (the story we already tell ourselves). Thus, people who have religious faith are more likely to believe in a story about a miracle. Soldiers who have trained for war and know the people they face are willing to kill them are likely to believe the story that the enemy is not like them and to depersonalize them into creatures it is okay to kill. They are not a human beings with emotions and values and families; they are “Japs,” “Chinks,” “Kikes.”

Survival obviously increases when you are able to kill an enemy before they kill you. But if we are convinced the “enemy” is among us, this kind of label-story allows us to hurt them with a free conscience.

It also apparently matters how often we hear a story. We humans are herd animals, at least in the sense that if we observe that a lot of people want something, we want it too. Trust me, advertisers make billions of dollars off of that principle. This also makes sense from an evolutionary standpoint. If everyone is running in one direction, our survival chances are higher if we run too and in the same direction.

These things are programed into our central nervous system.

TV evangelists have been using these story principles for a long time to bilk people out of their savings. Politicians use them to sway people. Stories repeated and appearing to be believed by others can influence people to act in a manner they might never have considered. Hitler told a story about how Germany could become “great again.” And how Jews were despicable and less than human.

Writers are powerful because they understand the power of stories.

Story is intrinsically neither “good” nor “bad.” Once we understand the principle, we are not compelled to believe it or act on it. We can compare it to facts we have confidence in. We can stop and evaluate the story being told, whether from others or from one of the “voices” of our own brains. We can decide to swallow it or change it or reject it. We can choose another story, tell ourselves another version. “I am a bad person” can become “I am doing the best I can.”

We have that ability, but only if we recognize that everything is story.

And that may be the most powerful thing to remember today.

T.K. is a retired police captain who writes Books, which, like this blog, go wherever her interest and imagination take her. Visit TKThorne.com