One of my cherished and vivid memories is a sweltering summer night in my hometown of Montgomery, Alabama. Although I was too young for a driver’s license, my father—never one to let little rules stop him—was teaching me to drive. Out of the darkness ahead, a bright headlight beamed directly into my eyes, blinding me.

“I can’t see!” I shouted, certain I was going to wreck the car and kill us both.

His calm voice at my side said, “Focus on the white line on the shoulder of the road.”

To my great relief, eyeing that line kept me on the road and eased my panic. Even now, whenever I lose sight of the road from oncoming headlights or a heavy fog or storm, I remember his voice and look for that line.

That brings me to a strange something I’ve been mulling about—the fact that, although I wanted to be a writer most of my life, I never had any interest in writing about American history, much less the civil rights era, even though my family played a role in it (a subject for another post) or perhaps because of that.

Wonder Woman was my childhood hero. Science fiction enthralled me as a young person (Heinlein, Asimov, Herbert). Then epic fantasy (Lord of the Rings, The Chronicles of Narnia, Dune) took hold of my imagination.

I confess that I still watch Marvel superhero movies.

Ancient history was interesting, even as a youth, because it was pretty much epic fantasy, particularly the pantheon of the Greek, Roman, and Norse gods. Where do you think the comic book heroes came from?

Thor, the “real” mythic Norse god of Thunder. Or Superman? (Hercules, anyone?)

There is a surface answer to why I wrote two civil rights era histories. In brief, a former Birmingham police officer/FBI analyst and a retired FBI agent asked me to write one of them. And four men who’d lived through the era in Birmingham and had sat for decades with the frustration of knowing important stories had been forgotten or never told, asked me to write the second.

That’s the simple explanation.

But the first book took four years and the second one, eight years. That’s a dozen years of my life. Kind of a long time for a didn’t-really-mean-to-go-there project.

One ought to self-examine.

Looking back on my life at this point, I have come to understand this: Curiosity is a major driving force of my psyche.

After contending with me in his 10th grade confirmation class, my rabbi wrote a poem in the form of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven,” only the refrain was not a raven quoting, “Nevermore,” but young Teresa asking, “Why?”

I suppose I should be flattered that I merited a poem from my rabbi. My chutzpah to debate with him on God’s existence as a fifteen-year-old must have simultaneously frustrated and bemused him.

Where did that chutzpah come from?

Hmm. In large part, methinks, my dad.

How fortunate I was that my father welcomed a rousing discussion at the dinner table and beamed with pride on the rare occasion I won a philosophical point. He taught me to always question the status quo and to look for alternative solutions to problems.

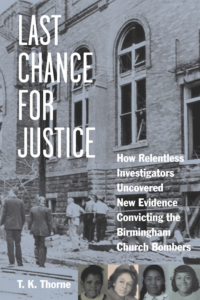

So, curiosity and the desire to tell an important story drove me to accept the challenge of writing those histories. Puzzling out a timeline and uncovering the unexpected kept me working on Last Chance for Justice— law enforcement’s behind-the-scenes tales of the investigation, trial, and conviction in the1963 Birmingham church bombing that killed four young girls and changed history.

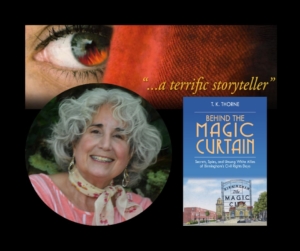

Counterbalancing the long haul of writing Behind the Magic Curtain: Secrets, Spies, and Unsung White Allies of Birmingham’s Civil Rights Days was the joy of learning overlooked facts and ironies about a time and people that has influenced my present.

But I never considered that anything much would come of the books other than my finishing them. After all, the tomes already written on the period overflowed my own bookshelf, and those represented only a partial offering of what others had penned.

When I woke from the “coma” of writing/researching, I found, to my genuine shock, that those books were relevant. How could that be? This was history. Gone. Past.

Nope.

Faulkner said, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

And Pulitzer prize-winning Alabama journalist, John Archibald, recently observed: “We’re moving forward fast. Right back to the past.”

It’s dizzying. Terrifying.

The world I have always thought of as a safe and forward-moving current carrying us toward more freedoms, more opportunities for all . . . is . . . .

At risk. Imperiled.

Where is Superman when you need him?

The headlights of oncoming nightmares are screaming in my eyes.

How do we move forward in this chaos?

I hear my father’s voice through time, as though I am still a young girl, panicked and overwhelmed.

“Just focus on the white line.”

Focus on where you are going. Write the stories you must write. Write the truths you must tell.

Thank you, Daddy.

T.K. Thorne writes about what moves her, following a flight path of curiosity, reflection, and imagination.

My partner and I went into a well-known restaurant in Birmingham, Alabama to eat dinner. We were working the Evening Shift (3-11 pm). Though we were both young female officers in the Birmingham Police Department, the shift sergeant had put us together to work a beat that included two housing projects, a couple of fast-food joints, and one “nice” restaurant—the one we walked into.

My partner and I went into a well-known restaurant in Birmingham, Alabama to eat dinner. We were working the Evening Shift (3-11 pm). Though we were both young female officers in the Birmingham Police Department, the shift sergeant had put us together to work a beat that included two housing projects, a couple of fast-food joints, and one “nice” restaurant—the one we walked into.