Slash & Burn: Or Just Rearrange a Few Words?

I stared at it, bracing myself.

It was a headline. It was subtle and chilling, and I couldn’t help wondering if I was complicit.

I stared at it, bracing myself.

It was a headline. It was subtle and chilling, and I couldn’t help wondering if I was complicit.

Well, this is something that doesn’t happen every day!

My brother had a “small planet” (asteroid) named after him! (I know I’m not supposed to overuse exclamation points, but I can’t help it.)

He earned this through his work on the New Horizons project—a NASA mission to study the dwarf planet Pluto, its moons, and other objects in the Kuiper Belt.

I am thrilled to announce [drum roll, please] the minor planet: Danielkatz!

I have a special appreciation of Pluto because many years ago, my first published short story (a big deal for a writer) was about an astronaut who crashed on Pluto. Here is a snippet.

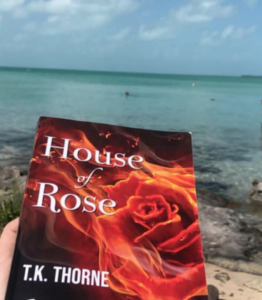

T.K. Thorne wanted to make first contact with aliens. When that didn’t work out, she became a police officer. Although most people she met were human, some were quite strange…. Retiring as a precinct captain, she writes full-time. Her books include two award-winning historical novels (Noah’s Wife and Angels at the Gate); two nonfiction civil rights era works (Last Chance for Justice and Behind the Magic Curtain: Secrets, Spies, and Unsung White Allies of Birmingham’s Civil Rights Days); and then she turned to crime with murder and magic in the Magic City Stories trilogy (House of Rose, House of Stone, and House of Iron). Read below to find out where her books have traveled.

A reader sent this picture from Belize! It was special to me because my husband had picked Belize as a place he wanted to go for our 20th anniversary. We stayed in a grass cottage in the heart of a tropical jungle. Howler monkeys woke us the first night at 3 a.m. We thought the world was ending! If you have never heard howler monkeys, horror movies used the sound for zombies!

One day, we climbed a steep Mayan temple for a breathtaking view over the jungle canopy. My husband had gotten a breathtaking view of my butt climbing ahead of him and thought it would be funny to take a picture. No, they never grow up, and no, I am not posting it!

The resort staff surprised us with a romantic anniversary dinner for us on board a pontoon boat and left us to float on the deserted lagoon by ourselves. Above, stars gleamed against a deep black sky like crystal dust. More than I have ever seen. I felt I could reach up and grab a handful. Then, our boat (which we had no way to steer) bumped into the shore and a mass of thick vegetation. Remembering the crocodiles we had seen on a previous night’s tour, we called for extraction.

A few days later, we transferred to Ambergris Caye. At home, before the trip, my husband and I had gotten certified in scuba diving, planning to dive into the Belize Barrier Reef. It’s the largest reef in the Northern Hemisphere, but it’s accessible with only about a 40-50-foot dive. However, before our trip to the reef, an opportunity arose to dive the famous Blue Hole, which would mean going down 150 feet, way deeper than we’d ever been.

The Hole is over 400 feet deep and wide enough to be seen by satellite! I had cold feet, but by the following morning, I decided this was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, and I would regret it if we didn’t go. We had to scramble to get headlights (it’s dark that deep down!) and make the group cast off.

Screenshot

At the Hole, we donned our gear and started down. I could feel the pulse beating in my temples as we went deeper and deeper. Strangely, there was no sensation of increasing pressure, but we were accompanied by a circling escort of sharks I only later learned were harmless nurse sharks. However, I also later learned that hundreds of divers have died in the Blue Hole, something I guess the sharks were aware of. . . .

At about 150 feet, we encountered the top of the underwater caves and swam around a three-foot-wide stalactite that plunged below us like a gigantic stone tooth, disappearing into the darkness. Not only had we descended into the water’s depths, but we had traveled through time. During the last Ice Age (about 10 – 19,000 years ago), the sea was below the cave floor, meaning 400 feet below the current sea level!

Though there was a tense moment regarding air supply, we made it back to the surface without becoming shark food. The next dive was the Reef, which was, in a different way, as dramatic as the Blue Hole. To my left, every square foot was crammed with diverse, colorful coral and marine life. I was mesmerized and could have stayed in one spot the whole time! To my right, the deep, almost black blue vanished into infinity.

We had other adventures, but too much to tell. So, when a reader sent the picture of my book as her beach read in Belize, it was a treat to learn Rose (the heroine of House of Rose) had also traveled there. I doubt her trip was similar to mine, but Rose had stuff to deal with:

When rookie patrol officer Rose Brighton chases a suspect down an alley, she finds herself in the middle of every cop’s nightmare—staring down at a dead body with two bullet holes from her gun . . . in his back.

He’s dead and now she has to explain it, which is going to be a problem because what happened was so strange, she doesn’t understand it herself. Rose must unravel the mystery of what happened and who she really is—a witch of the House of Rose. If she doesn’t figure it out fast, there will be more bodies, including her own.

House of Rose, set in the Deep South city of Birmingham, Alabama, is the first book of the Magic City Stories.

Also available as Audio Books on Amazon or Audible.com

“Thorne delivers a spellbinding thriller, an enthralling blend of real-world policing and other-world magic.—Barbara Kyle, author of The Traitor’s Daughter

“A deftly crafted and riveting read.”—Midwest Reviews

“Thorne, a retired captain in the Birmingham PD, grounds the fantasy with authentic procedural details and loving descriptions of the city and its lore. Readers will look forward to Rose’s further adventures.”—Publishers Weekly

“T.K. Thorne is an authentic, new voice in the world of fantasy and mystery. An explosive story that will keep you on the edge of your seat. Pick up this story—you’ll thank yourself over and over again.” —Carolyn Haines, USA Today bestselling author of the Sarah Booth Delaney, Pluto’s Snitch, and Trouble the black cat detective mystery series

“Although House of Rose is speculative fiction, a kind of fantasy, T.K. Thorne is so knowledgeable about Birmingham and law enforcement that it is also, truly, a police procedural and a thriller—something for everyone. “House of Rose” is the first of a series which should be a hit.”—Don Nobles, reviewer for Alabama Public Radio

I just read an article about the importance of connecting or reconnecting with our playful selves. “It offers a reprieve from the chaos.”

That sounded intriguing. There is certainly a lot of chaos going on at the moment. I could use a reprieve.

When we were children, we didn’t play to accomplish anything. We just played. Explored. Play = fun. Fun was an end goal. We didn’t post stuff we did to social media or analyze what we learned. We just played. Learning was the byproduct of curiosity.

If I may borrow a biblical phrase—And it was good.

But who knew there were personality play traits?

One study broke preferences down into four categories:

Our play as adults adapted from what we naturally enjoyed (our play preference) as children. Some adults, for example, “seek fun through novelty, whether it’s traveling to new places, exploring new hobbies, or buying new gadgets.”

“List the activities you enjoyed as a kid,” the article suggested, “then brainstorm the grown-up version.”

So, here goes:

I liked to climb trees. I had a special tree in the front yard, a young live oak with inviting arms that was my special place to go when things got tough, or I wanted a different perspective, or a steady, quiet friend. There was also the top shelf in the tiny linen closet that had an antique oval glass window where I could look out at the world, but no one could see me.

I rode many amazing chimera horses that were my legs, jumping over logs, chairs, bushes, and anything in my path. And if there weren’t enough things in my path, I would put them there to jump over. (Would you believe that is a sports competition now with adult people? It’s called “hobby horsing!” ) I currently have three real horses in my yard, but they think they are living at the Horse Retirement Riviera, and I doubt “jumping” anything is on their play list.

I did have a Barbie doll, but she was in reality a prop for my plastic Breyer horses. To my annoyance, she could only ride sidesaddle with her legs sticking out straight. I draped my horses in my mother’s costume jewelry and had them interact in elaborate storylines, often without the interference of people characters. Who needed them?

Screenshot

Lest you think me a hermit, in the first decade of my life, I did interact with others in play. I remember games of Red Rosie, tag, touch football and kickball, but when we didn’t have enough people for that or were too young to join in, I participated in impromptu gatherings where we acted out scenarios. I was usually the bossy “director.”

“You are the prince. And you are the princess. And you are the merchant. And you are secretly in love with the queen and, oh yeah, I am the queen….”

Hmm.

At least in part, intellectual play seems to have appealed to me. That sparked this idea:

Maybe I need to look at writing, not as a chore TO DO, but as a chance to play.

I like that.

So, hang on. We’re just playing here.

When I write, I often use two of the most powerful words that I know of. They open doors into imagination, exploration, and . . . play.

They are (cue drum roll)—

“What if . . . ?”

What if I just thought I was a serious writer, but I am actually just playing?

[Laugh of delight!]

How did you play? Is there a way to replicate that now, to permit yourself to do something just for the joy of it?

*The results of my adult play:

*The results of my adult play:

![]()

I write about what moves me,

following a flight path of curiosity, reflection, and imagination.

Check out my (fiction and nonfiction) books at TKThorne.com

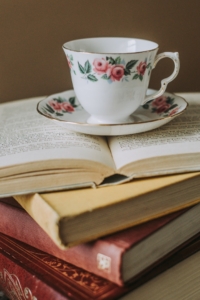

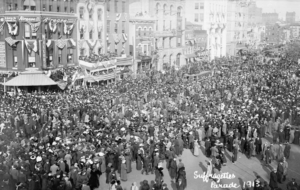

Who knew? The women’s movement to win the vote in the United States (which didn’t happen until 1920) began with book clubs! In my life, “feminism” was a word often expressed with a sneer, the struggle for equality seen as an effort to shed femininity and be man-like. Burn your bra at the peril of rejecting your womanhood!

In my life, “feminism” was a word often expressed with a sneer, the struggle for equality seen as an effort to shed femininity and be man-like. Burn your bra at the peril of rejecting your womanhood!

But my role model, my mother, was as feminine as they come and yet stood toe to toe with men in power. She never finished college, having to quit to care for her ill father, but she continued to learn and read and surround herself with other women who used ideas and knowledge to challenge the status quo, a legacy that began long ago.

Despite the pressure on women to focus on family and household matters, women throughout history have organized to read and talk about serious ideas, even in the early colonial days of American history. Anne Hutchinson founded such a group on a ship headed for the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1634. Reading circles or societies spread throughout the 1800s, including the African-American Female Intelligence Society organized in Boston and the New York Colored Ladies Literary Society. The first known American club sponsored by a bookstore began in 1840 in a store owned by a woman, Margaret Fuller. In 1866 Sarah Atwater Denman began Friends in Council, the oldest continuous literary club in America. In the South, blacks slaves were punished, sometimes with their lives for learning to read or if they were found carrying a book, although some surely passed books and abolitionist tracts in secret, despite the terrible risk.

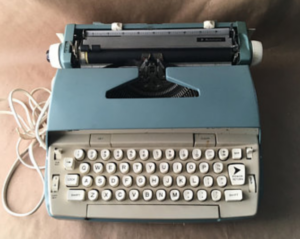

Mandy Shunnarah wrote about research she did on this subject in college, sharing how the turn-of-the-century women began with classical ancient history and gradually became informed about political and policy issues of the day. The clubs created opportunities for connection and community and provided a conduit for organization and action. Undoubtedly, progressive organizations like the League of Women Voters, which formed in 1920, were an outgrowth of those clubs. My mother, Jane L. Katz, was a longtime member and a lobbyist for the Alabama state League of Women Voters. I have memories of her sitting at her electric Smith-Corona and typing away at tedious lists that tracked status and votes on legislative bills of interest to the League—education, the environment, constitutional reform, judicial reform, ethics reform, home rule.

My mother, Jane L. Katz, was a longtime member and a lobbyist for the Alabama state League of Women Voters. I have memories of her sitting at her electric Smith-Corona and typing away at tedious lists that tracked status and votes on legislative bills of interest to the League—education, the environment, constitutional reform, judicial reform, ethics reform, home rule.

I remember her taking me to a site to show me what strip mining actually looked like when a coal company was finished ravaging the land. She worked hard for the Equal Rights Amendment, which had as much chance of passing in my state (Alabama) as a law against football. I followed her to the state legislature while she talked to white male senators about why a bill was important and I will never forget how they looked down at her condescendingly. It made me angry, but she just continued to present her points with charm, wit, and irrefutable logic. The experience turned me off to politics, but gave me a deep respect for my mother. I know she would be saddened that many of the issues she fought for have yet to come about, but she would be proud of today’s many strong women’s voices speaking up for the values she so believed in and fought for. She and my grandmother began my love of reading and books. Today, it’s estimated that over 5 million book clubs exist and 70-80% of the members are women.

A special childhood memory is my parents chuckling over a New Yorker cartoon my father cut out and showed to friends—Two stuffy businessmen are talking quietly. One says, “But she is a mere woman!” The other replies, “Haven’t you heard? Women are not so mere anymore.”

I’m not a politician. I’m a writer. My mother died decades ago, and sometimes I feel guilty not following in her footsteps. But I think she would have been proud that the women in my books are not “mere.” And I am proud and excited that I might see in my lifetime an exceptional woman in the White House. I even dare to hope it might change the world.

Whether that time is here or not, it is a gift and a closing of the circle connecting me with my mother and all her predecessors to know the heritage of feminist activism—the striving for a society where women’s thoughts, ideas, and work are equally respected—began with a group of women, perhaps a cup of tea, and a book.![]()

T.K. Thorne writes about what moves her, following a flight path of curiosity, reflection, and imagination. Check out her (fiction and nonfiction) books at TKThorne.com

We are perplexing beings.

I just finished reading Maus, a graphic book by Art Spiegelman banned in Russia and Tennessee. The author’s words and drawings depict his attempt to capture his father’s memories of living through the Holocaust. The young man is conflicted, unable to stand being around his eccentric, obsessive father and overwhelmed by what he learns his father experienced. It is raw and honest. I recommend it.

What seems unthinkable and impossible to understand is people believing other people are not human beings but vermin to be used and extinguished. That is what the Nazis believed, what slaveholders believed, and what many neo-Nazi white supremacists still believe. I imagine some members of minorities feel similarly. I don’t understand what Christian Nationalists believe other than America should be for them only. I’m unsure what they plan to do about the rest of us.

And that’s the point. We are all human beings.

We think and do these extraordinary thoughts and behaviors because we evolved not as rational beings but as emotional ones. Fight/flight and survival are our primary, cell-level drivers, not rationality.

Rationality is an overlay, a wobbly gift of the last layer of the brain to evolve—the neocortex, which contains the prefrontal cortex, where we analyze, plan, and make decisions based on reason rather than raw emotion. Emotion ran the show before that development. Emotion plays a vital role in behavior. (Danger = run or fight.) But reason developed to increase our ability to survive. If we observe and learn what has happened in the past, rationality allows us to predict the future, and we have a better chance if we can prepare for the future.

But that can go sideways.

For example, people around us can believe wacky things. Those things may not make sense if we examine them closely, but we are driven, for one thing, to please those important to us. We need to be part of a group/clan/family. It’s a hard-wired survival instinct. At some point in our history, we could be kicked out for not complying with the group. “Kicked out” meant the wolves ate you.

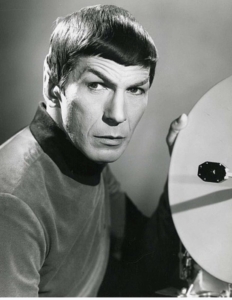

And, alas, we are not Vulcans. We easily slide into tribalism and can believe all kinds of stuff, regardless of its basis in reality (whatever that is, but that’s another story). Science has proved that a brain under enough stress will break. Any brain. All brains. (Snapping, America’s Epidemic of Sudden Personality Change, 1978, 1995 Conway and Siegelman)

Humans are a fraction of the last second before midnight on the 24-hour clock of our Earth’s existence. And we “just” developed our cerebral cortex. We aren’t sure what to do with it except write books (Yes!) and play with our toys. That play has created some wonderful, amazing things. There appear, however, to be some “whoops” attached to those wonderful things, like the possibility of screwing up the Earth and annihilating ourselves with our toys.

So, (1) we are not primarily rational beings, and (2) we are very young.

Is there hope for change?

Trying to apply rationality to answer that question (instead of my emotional instinct), I would say -YES. If it is true that we are not primarily or originally rational beings, it is also true that we are headed (however slowly) in the evolutionary direction of rationality. The fact that we are a very young species also implies that, with time, we will continue to add functional brain capacity that will nudge us toward traits that increase our survival ability.

The question is, will we survive long enough to get there?

In the current day, it is hard to imagine such change when terrorist organizations indoctrinate their communities with hatred from birth. Despair feels like the rational expectation.

But then there is what happened in Germany after WWII. Although the Nazi doctrine is far from dead (either in that country or others, including the United States)—their ideals are no longer mainstream.

By all rights, Japan should hate Americans after we dropped two atomic bombs on their civilian populations. They do not hate us. We are global partners.

Maybe there is hope for change.

But how do we change now without having to wait for evolution’s slow grind, the coin toss of whether someone pulls the nuclear trigger, we push the climate to a state of disaster, or maybe we all choke on plastic?

Jeddu Krishnamurti, an Indian philosopher, says we must first understand that we are connected to and, in a real sense, are all human beings.

He writes:

“To bring about a different society in the world, you, as a human being who is the rest of humankind, must radically change. That is the real issue, not how to prevent wars. That’s also an issue, how to have peace in the world, [but] that is secondary. . . the fundamental issue is—is it possible for the human mind, which is your mind, your heart, your condition, is that possible to be totally, fundamentally, deeply transformed?

Otherwise, we are going to destroy each other through our national pride, through our linguistic limitations, through our nationalism, which the politicians maintain for their own benefit, and so on and on and on.”

Krishnamurti suggests that the path to transformational change involves deep listening—to others, ourselves, and nature.

What is deep listening? I am not sure. I think I do it when I’m writing and allowing a character to truly be themselves. I think I do it when I pause to breathe in the scent of earth and bird song. When I allow the decision of compassion to guide me. I know a whole list of things it is not.

“Truth is a pathless land. Man cannot come to it through any organization, through any creed, through any dogma, priest or ritual, not through any philosophical knowledge or psychological technique.”

So, how do we find the truth that will free us from ourselves?

Let’s begin by turning our attention and focus to deep listening. We may not know exactly how to do it because it is a pathless land. And we will need to try repeatedly because we are all flawed human beings. But maybe we really can change. The first step is believing we can, believing that humanity can survive to become wiser, use our tools, toys, and our resolve to improve the world, and learn to cherish it, ourselves, and each other.

Maybe.

I hope we can. I hope we try.

![]()

T.K. Thorne writes about what moves her, following a flight path of curiosity, reflection, and imagination. Check out her (fiction and nonfiction) books at TKThorne.com

Writer, humanist,

dog-mom, horse servant and cat-slave,

Lover of solitude

and the company of good friends,

new places, new ideas

and old wisdom.

What kind of world allows young American football players to feel comfortable making a video about raping an unconscious girl? A world where the defense against a brutal, fatal rape of a student in India is that “respectable women are not raped?” A world where a young Pakistani student is shot for going to school?

The brutal actions on Oct 7 shocked us, yet there are daily attacks on women throughout the world. Not to mention the massacre of children in schools.

What do these two subjects—violence against women and mass shootings—share? They are both about power.

In most individuals, most of the time, the drive to power funnels into positive channels—a determination to make a business successful; craft an environment that ensures the best future for our children; cure disease; explore space or the ocean or the world of the quantum; render a painting that reflects our deepest emotions; or find the words that move a reader. That is power.

There are also negative channels—the malicious release of a computer virus, the poisoning of trees: the sabotage of a fellow worker; the punch of a fist; the pulling of a trigger; even when the gun is aimed at the aggressor’s own head. These acts are also efforts to establish or regain power.

Why do we struggle so to be the master of our environment, our emotions, or influence?

Survival.

In the millennia that shaped us, if we were not wired to seek power, we would have been eaten. In another post, The Most Important Question, I explored the question of whether our basic nature has evolved since we became “human.” Recently, a research project added to that discussion when scientists found that the human hand, so intricately designed to manipulate and experience the world was also uniquely evolved to become a weapon, as a fist. We aren’t going to erase our nature, and if we did, we might loose all the best that we are or can be in the bargain.

What we can do, what we must do, is civilize ourselves with laws and education and support safety nets. We need to make abusing power, be it physical, emotional or political, unacceptable; to encourage a world where “success” is culturally defined by making the world a better place.

![]()

T.K. Thorne writes about what moves her, following a flight path of curiosity, reflection, and imagination. Check out her (fiction and nonfiction) books at TKThorne.com

This is a true and funny story that happened a few years ago. It’s about angels and life and Bob.

I was thrilled that my book had won a national award but didn’t think it was worth a trip to Chicago just to get a photo made. Sister Laura, however, was hyped about it. She had worked hard with little credit—editing, designing the original awesome cover, marketing, and supporting me at every step of my novel about the wife of Lot (Angels at the Gate). She also wanted us to attend the BEA (Book Expo America), which was happening simultaneously.

A few days before our flight, Laura fell and hurt her ankle. BEA requires lots of walking, but she was determined to go, even if she had to get a wheelchair. Where most people would have rented one, my always-check-a-thrift-store-first sister borrowed an old wheelchair from a thrift store. It was heavy and squeaky, and not knowing its history, she had cleaned it with Lysol, which was a prudent sanitary move but, unfortunately, set off the explosive-substance detector at the Birmingham, Alabama airport.

So, wheelchair, Laura, and all of her stuff had to be hand searched. And they confiscated our wheelchair, in case it was really a bomb, I guess, promising it would be at the gate waiting for us when we arrived in Chicago.

Not.

No wheelchair at the gate when we landed in Chicago. Had it exploded somewhere? We finally track it down in baggage. After a start like that, we are surely over the hump. All we have to do now is get outside the terminal because Laura has arranged for her friend, Bob, to pick us up. I’d never met Bob, but he was Laura’s friend. What could go wrong?

Bob, it turns out, is 82 years old. His car is about the same age and smells strongly of gasoline. I have visions of someone in front of us throwing out a lit cigarette. Are we going to explode after all? Will the Lysol on the wheelchair add to the incendiary mix?

Bob hops out and loads us up, pulling stuff randomly out of the hatchback area to get our suitcases and the wheelchair in and then crams piles of boxes on top of them, keeping the hatch down with bungee cords. When we get in the car, I politely mention that the boxes totally block his vision on one side.

“I’m used to it,” he says, pulling out into the rain and the insanity of the Chicago airport traffic.

The “it” he is “used to,” I realize, is not being able to see . . . omg!

I text our hostess. *Landed. If we survive Bob, will be there soon.*

Miraculously, Bob gets us where we are going, an area several miles north of Chicago in Edgewater, where Laura has arranged rooms at a friend’s cousin’s condo. Why, my always-check-a-thrift-store-first sister had reasoned, stay at an expensive hotel? It is a lovely place, but this is the award night, and I am worried about us getting back into Chicago. That ride was not part of the Bob-bargain, so we are on our own. That’s a good thing, right?

At Laura’s insistence, we forgo a taxi because we are so far away, but Laura has called the Chicago Transit Authority, and they assured her that all the metro train stations are handicap accessible. Still, it is no longer raining, and we leave the condo early, me pushing the squeaky, cumbersome wheelchair that I learn randomly applies its right brake and jerks hard to the right. I should have had a clue that the plans made by a woman who borrowed a wheelchair from a junk shop, not to mention, Bob, might warrant follow-up. When we arrive at the nearest station, we find there is, indeed, a way to get a wheelchair into the station. But “handicap accessible” does not stretch to a way to ascend the many stairs to the subway platform.

Reversing course, we head to next station down the line, which does have an elevator and where we meet a nice young man with the Chicago Transit Authority who helps us up to the platform. I ask his name.

“Angel,” he says.

My first thought is how appropriate—the name of my book is Angels at the Gate! WAIT! The name of my book. . . omg, I have forgotten a copy of my book (necessary to hold when getting picture taken at awards.) The last thing the publicist said was, “Don’t forget a copy of the book for the photo.”

I leave Laura on the platform with Angel, hurrying back to the condo. By this time, my feet are aching in my boots (which I am wearing because my skirt rises too far in front for knee-high stockings, and I will die before wearing pantyhose.)

I grab a copy of my book and switch my boots for sandals. Still need the socks, because this is Chicago, not Birmingham. I look down to see two bright pink big toes peeking out through holes in the socks.

Whoops, sandals not going to work for photo opt. I grab boots for later donning. By the time I get back, we are running late. We set the brakes on the wheelchair but, besides randomly engaging, they are not that spiffy about staying engaged. At the first lurch, Laura rolls down the aisle. I am running after her trying to catch her before she crashes at the other end.

A second angel jumps from her seat and shows us how to lock in the wheelchair. Who knew? We are from Alabama.

The clock is ticking. The whole purpose of the event is to get that photo op. We are a long way from our stop, the closest one to the (Sears) Willis Tower with an elevator.

As we discuss strategy for when we exit, a third angel pops up from her seat—apparently getting a signal from above (or perhaps watching our entrance) that there are some Alabama girls in need of assistance—and plops into the seat next to me.

“You’re going to Willis Tower? I work near there.” She kindly explains which way to walk from our next stop. We are so late now that we must take a cab.

Holding our breath against the olfactory assault in the train elevator (known as a subway by locals, even when it is above the ground), we descend to the street. I step out into the roadway and hail a cab for the first time in my life. (Again, I live in Alabama; a household is incomplete without two cars and a pickup truck.) A cab stops and looks us over, shaking his head at the wheelchair and driving on. I hail another cab, who also shakes his head at the wheelchair. We push on to Willis Tower, rolling through the puddles and treachery of cracked sidewalks. We are now very late.

I push the rickety wheelchair as fast as I can until we hit a crack in the sidewalk that stops us dead, shoving the wheelchair handles into me and nearly dumping Laura, book, and boots onto the sidewalk into a puddle because, yes, of course, it is now raining again.

Willis (Sears) Tower is massive. We enter and proceed via elevator to a winding corridor down to the security station, surely close to our goal, only to find we are at the wrong door and have to be escorted through the labyrinth of the Tower to the service elevators in order to reach 99th floor and the Independent Publisher’s party and awards announcement. We are finally here! We register, pick up our ID’s and a program . . . from which we learn “Historical Fiction” is #15 on the list and they are now announcing #26.

We missed it. All the way from Alabama to Chicago . . . and WE MISSED IT!

I wheel Laura to the bathroom. I feel worse for her, since she really wanted this, and it is as much her award as mine because cover design and layout are also considered, along with the story and writing.

While waiting for her, I notice we are sort of “backstage” to the awards announcer, and a beautiful young woman is standing (on the stage) with her side to me, so close I could touch her with a step. She is obviously connected to the proceedings. Hearing one of my father’s oft-repeated life lesson in my head— Only the squeaky wheel gets the grease— I take that step and tap her shoulder between photo setups, whispering that we had difficulties and just arrived, and is there any way we could go out of order? She steps out of the big room and consults a list, asks my name.

“T.K. Thorne.”

She brightens. “Oh, you are T.K. Thorne? I loved your book!”

“You read it?”

“Yes, I really loved it; it was my favorite book out of all of them.”

There are 80 national categories. No idea how many submissions in each category or how many she actually read, but that’s a lot of books, even if she meant in my category. As far as I am concerned, I am happy.

Dianu. (Hebrew for “it is enough.”)

She graciously arranges for us to get called up, Laura hobbling at my side. They put a huge medal worthy of the Olympics around my neck and, to my delight, around Laura’s too. And I have the book in hand! Success! Photo snaps.

You wouldn’t have even seen the pink toes. We head to the bar.

View out the Willis Tower, drink in hand View out the Willis Tower, second drink in hand

Over the next several days we encounter angels and references to them in rather odd ways. In addition to the transit guy named Angel, another “angel” (whose friend is Angela) shows me how to use Uber (Yea! No more wheeling for blocks to the train station); the Egyptian uber driver mentions his son’s name is translated as “Angel in Heaven”; and a book publicist at the Book Expo America (BEA) advises me to “listen to my angel.” I keep looking for a flutter of wings out of the corner of my eye!

On our last day, Bob picks us up, and we load wheelchair and baggage. After bungee-cording his car hatch down (not because of our luggage, just normal procedure), we are off to the airport with an extra hour . . . just in case. It is bitter cold, but I roll down my window because I can’t afford losing any more brain cells from the fumes. There is so much stuff in this car, it is unidentifiable. I try not to think about what all could be in there and just hope there are no rodents that live near my feet. This time I am in the back seat, and I reach for the seat belt. I actually find one, but there’s no buckle, so I just loop it around one shoulder. There’s a chance if we hit something at just the right angle, it might help. Laura is in the front seat. “What’s that noise?” she asks, forehead wrinkled in concern. Is it the engine?

“I don’t know,” Bob says. “Haven’t heard that one before.”

Laura: “Sounds bad.”

Bob: “Unless the wheels fall off, I usually just turn up the radio.”

I couldn’t make this up.

Postscript: Despite appearances, Bob was one of the many Chicago angels, for sure. He has spent most of his life traveling around the world helping people in disasters, which is how he and Laura met. I really wish I could spend more time with him and hear his stories . . . just not in his car.

![]()

T.K. Thorne writes about what moves her, following a flight path of curiosity, reflection, and imagination. Check out her (fiction and nonfiction) books at TKThorne.com

Susan had never told her family about her experiences. In fact, before Louisa Weinrib called her in 1990 for an interview, she she had never talked about what happened to anyone other than those who had gone through it with her. Hers is a true story of amazing strength, resourcefulness, and friendship.

Susan Eisenberg’s childhood was full of promise. An only child, she was born in 1924 into a family that proudly traced their Hungarian lineage back a hundred years. She grew up in the small town of Miskolc, where her father had a successful business buying and exporting livestock and grains for a farming cooperative.

Susan was aware of anti-Semitic sentiment, but it didn’t touch her early life. The Jewish community was well integrated into Hungarian society, and she had many Christian friends. She spoke Hungarian and German, loved to ice-skate and ski, and wanted to go to college, but by the time she was of college age, Jews could not attend.

Her loving and close-knit family gathered after synagogue at her home, where they also celebrated the Seder. On weekends, they offered a tradition of high tea for family and neighbors.

Trouble began in 1938 with a small Hungarian Nazi party that grew in strength, paralleling the party’s growth in Germany. After Germany’s invasion of Poland in 1939, Polish refugees fled into Hungary, bringing what seemed unbelievable stories of what was happening in Poland. Without a birth certificate validating birth in Hungary, officials shipped the fleeing civilians back to Poland. An army friend confided to Susan that, in reality, the Poles were taken across the border and shot. Even when people began wearing brown shirts with swastika armbands and spouting slogans, Susan recalled, the Jewish community just ignored it.

In 1940 Hungary became an Axis power. Hitler, who invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, demanded that Hungary join that war. Susan’s uncle died when he was forced to walk with others into a field between the German and Russian armies to test for the presence of land mines. Her father was taken to a work camp. Released the following year, he was ill and depressed and died soon after at 44. After his death, Susan and her mother moved to the city of Budapest to live with relatives.

Although the Jews in Hungary suffered under tightening restrictions, Hungary’s regent protected them for a time from Hitler’s “final solution”—extermination—until Hitler discovered the regent was secretly negotiating an armistice with the US and the UK. On Easter Sunday in March 1944, Susan was having coffee with a friend on a cafe terrace and saw German panzer tanks rolling over the bridges into Budapest. The Germans occupied and quickly seized control of the country.

The Nazis rounded up her family members who were still living in the countryside. The relatives sent postcards—which Susan and her mother later learned the Nazis forced them to write—advising they were well and going to Thersienstadt (a concentration camp/ghetto in Terezin). All of them perished in that camp.

In Budapest, Allied forces regularly bombed the city. Everyone carried bags of food at all times, never knowing when they might have to run into the air-raid shelters. Jews were required to wear a yellow star patch on their clothing and live in designated housing. Restrictions dictated when they could leave the house and forbid them to go to public parks or even walk on the sidewalks. They could work only in manual labor positions. Jewish professionals, doctors and dentists, could only practice on Jewish patients.

Susan was 19, with light blonde hair and blue eyes. She pulled off the yellow star from her clothes and snuck out into the country to get food. Once, on her return, Germans soldiers in a vehicle, not realizing she was a Jew, picked her up. They asked for a date. Heart pounding, she agreed, lying about where she lived, and promised to meet them later. Safely home, she looked down at her clothes and realized that a closer inspection would have revealed the stitch holes from the star she’d removed.

When the Russian army was approaching Budapest, the Hungarian Nazis ordered Susan to report for labor with her age group and sent them to dig foxholes. Their Hungarian Nazi guards were 14 or 15-year-olds. When a young girl working at Susan’s side sat down and cried for her mother, those guards immediately shot her.

For two days and nights in the cold and rain, with no food, the guards ran them back to Budapest to work in a brick factory where she met two girls her age, Ferry (Ferike Csato) and Katherine (Katherine Goldstein Prevost). Susan pretended to be crippled and part of a group of sick and injured destined for Budapest and death. She escaped and made it to her aunt and uncle’s house, but the following day Hungarian gendarmes (police) rounded her up with others. The gendarmes forced even mothers from their babies to join with those in the streets.

Their Hungarian guards told them they were taking them to Germany to die. “The one who dies on the road is lucky,” they said. Over a ten-day period in October, they walked in rain, ice, and cold from Budapest to the German border (125 miles) to Hegyeshalomover. Thousands were shot for lagging behind or collapsing. A few country people along the way gave them a piece of bread. Others stripped them of their clothes. Guards kicked them. They slept in flea-invested hay.

Anyone who had anything of value traded it to the peasants for food. They fought for a share of rare carrot or bean soup.

One night, the guards packed them onto a barge on the Danube River. Overwhelmed by the press of dying people, Susan escaped by swimming to the bank in the freezing river. She begged a man she encountered to help her or just get her something dry to wear. He agreed but instead returned with police who escorted her back to the prisoners.

At the German border, they marched another ten miles to trains. Jammed into cattle cars, they traveled for days but couldn’t see out because black slats covered the cars. She was only aware of repetitive stopping and starting.

Finally, in October 1944, the trains arrived at Dachau concentration camp in Germany, their destination. The smell of the crematorium camp would stay in her nostrils for the rest of her life, as would the shock of her first sight of the skeletal prisoners who mobbed them, begging for bread. Guards beat the prisoners back.

The newly arrived assembled in a large open field, waiting to go in. But even with bodies being constantly cremated, there was no room for them in Dachau. Susan and her two friends, Ferry and Katherine, went with other girls to Camp Two and then Camp Eleven (nearby work camps). They slept in bunkers below ground on a wooden floor and a pallet of straw. Camp Two, they quickly learned, was the “sick camp.” The next stop for Camp Two occupants would be the crematorium in Dachau.

At the satellite camps, they were given striped uniforms. About 500 people lived in each barrack with a block leader in charge. Food came once a day in a big wooden barrel with hot water and big hunks of sugar beets. At night they received a piece of bread that “oozed sawdust and a piece of artificial marmalade.” At first, she couldn’t swallow it. The older inmates encouraged her to “eat it, no matter what.”

Each day, the prisoners were called out to stand, sometimes for hours, in the cold for a count and work assignments (Appell). “If you fell out, you were beaten or shot. If a friend was dying, you made sure that she stood up, no matter what, and wasn’t left in the barracks.”

In the first Appell, Susan was picked to work in a kitchen where she peeled beets. Germans brought in prisoners for punishment, hanging them from rafters and beating them. She and the kitchen workers constantly cleaned the blood from the floors. She hid beets inside her baggy shirt and shared it with her camp mates and the Muselmann—the starving, skin-and-bones prisoners resigned to their impending death.

Susan was transferred to different camps for work assignment. At one, German engineers of the Wehrmacht (Armed Forces), instead of SS troops, ran the camp. More humane, their military task masters distributed pieces of food to the workers, food that kept Susan alive. Barehanded and dressed only in the thin striped uniforms and sockless wooden clogs, Susan and her fellow prisoners pulled wagons of wood in the Bavarian winter mountains. Sometimes she was taken from the camp to wash clothes for German housewives. She also worked in the Sonderkommando (work groups at crematoriums) to remove teeth from the corpses of the murdered for the gold fillings.

Her health was deteriorating. She had lost weight and suffered from reoccurring high fevers. Typhoid broke out in the camp. There was no medication. To isolate the prisoners, the guards stopped letting them leave, throwing beets and bread over the fence.

In early March 1945, after the epidemics, a female guard beat her for speaking defiantly to a camp commander. People all around her were giving in to despair, but she refused to do so, vowing she would survive.

At another work camp, Susan joined women prisoners building an underground airplane hangar. They were forced to carry 100-pound bags of cement across a catwalk several stories high. The Muselmann went down instantly under the burden, falling to their deaths. “There was,” Susan said, “as much blood and flesh in that hanger as cement.”

An inmate orchestra played as she and other workers left the camp and on their return. Guards made the orchestra watch and play during beatings and hangings and while starved prisoners–who had tried to grab potatoes from a wagon—were strung up between the electrical barbed wire, potatoes stuck in their mouths.

Once, the Germans spruced up a barracks, putting in furniture and stocking it with people they found “not in terrible shape” for the Swiss Red Cross, who had come to inspect the treatment of prisoners. As soon as they were gone, the Germans took the untouched piles of canned foods, condensed milk, and chocolate the Red Cross had left for the prisoners.

One barrack’s occupants were expectant mothers. They were allowed to give birth to their babies and tend them. Then one day, without warning, all the infants were taken away and the women sent to the work groups.

To use the open trenches to relieve themselves, Susan had to walk through knee-deep mud at night, sometimes stepping on top of the bodies of those who had fallen there and died in the mud. Survival, she knew, depended on not allowing yourself to feel and thinking only of the moment.

Her last assignment was in a dynamite factory. By this time, the air raids were almost continuous. Landsberg, a nearby town, was under siege by the Americans. In April 1945, guards took her and her friends to the main camp in Dachau. They spent a night in the showers at Dachau, believing they would next be taken to the crematoriums, which were still “going strong.” But the next day, with thousands of young people, they were marched out of the camp. As they left, they could see the trains that continued to bring prisoners from other camps [to keep the Allies from discovering them], many already sick and emaciated. When the doors opened, dead bodies fell out. Inmates stacked them like mountains in front of the crematoriums to be burned. But the Germans had run out of time. The American guns were days away.

They marched from Dachau, walking at night and hiding in the woods during the day. Allowed to dig in the fields they passed for roots and potatoes, they ate them raw. All understood the guards’ orders were to march them into the mountains and kill them in the forests where the Allies would not discover their bodies. Guards shot in the head anyone who lagged or fell. Susan was sick and feverish. She could not walk on her own, but three friends, Katherine, Ferry, and another supported her, keeping her from collapsing.

As they struggled through the mountains and meadows of Bavaria, guards began deserting in the cover of night. American planes flew low enough Susan could read the insignia on the wings. The pilots, who surely saw the striped uniforms, refrained from dropping bombs.

Five days later, what remained of their group arrived at a work camp for Russian prisoners in the small German town of Wolfratshausen. The first task of their remaining Nazi guards was to take the Russian prisoners of war and shoot them. Knowing they were next, Susan lay on the roadside, too sick and exhausted to react. Then she heard a roar—the first American jeep of the Third Army coming down the road—liberators.

The German guards fled, but the liberators were combat troops, unable to care medically for the freed prisoners. The Americans moved on, and the liberated were left to fend for themselves.

Typhoid once again thinned their ranks. Her friends held out tin cans for food the passing American soldiers threw to them. Survivors that were able, brought supplies from the town and cooked soups. Reports that Americans fed and clothed German prisoners, playing baseball and basketball with them in the prison camps, ignited bitterness and anger. Many Jews took abandoned weapons and hunted the German SS who had tortured them and killed their friends and families.The sound of gunfire in the surrounding forests peppered the nights.

They spent the summer in the woods, slowly regaining their strength, then Susan, Katherine and Ferry trekked to a displaced persons camp. Although her friends wished to immigrate to Israel, Susan wanted to go home to Hungary. And they chose to go with her.

They walked to Prague, a journey of 145 miles, where a Russian troop train allowed them to ride. Arriving finally at their destination of Budapest, they found it devastated. Susan couldn’t find her house in the rubble . . . or her mother. They tried to find work. Inflation made money worthless. A friend of her uncle finally gave her a job in the ministry [government] which paid the workers in potatoes and bread. They lived in a room open to the elements; bombs had destroyed the windows and doors.

Ferry convinced Susan to go with her, Katherine, and two Sabra (Israeli) agents who were attempting to get fifty Polish Jewish children to Israel. The children had survived by hiding in Christian homes. Susan and her friends rode with them by train to the Hungarian border where they had to walk about 200 miles.

The friends, with the two Sabra agents and three other men, accompanied the children through heavy snow in the fields and woods. Twice, they paid off Russians who stopped them, but the third time, at the German border, they had to make a run for it. They abandoned all their belongings in their dash for freedom. Older children carried the younger ones. Russian bullets followed them. Once safely across, the children continued through Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Cyprus and then into Israel. But Susan still did not want to go to Israel.

Later, Susan said she regretted that decision and felt pride in what Israel stood for. “You know, even if you have to die, if you die on your feet fighting, it’s a heck of a lot different than to be shoved into a gas chamber [to] die like mice or cockroaches, or whatever.”

Susan lived in Germany for three years, then married a GI and came to America in 1948, becoming a U.S. citizen. She had two children, Diane and Leslie, and lived on Long Island, NY. Struggled with multiple health issues, she worked in various factories to pay her medical bills before getting a clerical job on Mitchel Air Force Base, which turned into a civil service career of 30 years.

She divorced and eventually married another serviceman. With his transfer to Maxwell Air Force Base, they moved to Montgomery, Alabama.

Ferry and Katherine joined relatives in America, and the three friends kept in touch for the rest of their lives. Finally locating her mother, who had returned to Budapest, Susan brought her to Montgomery in 1956.

Susan Petrov Eisenberg died in Montgomery, Alabama, in 2008.

Note: I had the privilege of compiling Susan’s story. She was one of the survivors who made Alabama their home after WWII. Others’ stories and a wealth of educational material about survivors and the Holocaust is available at the Birmingham Holocaust Education Center website—bhecinfo.org

T.K. Thorne writes about what moves her, following a flight path of curiosity, reflection, and imagination. Check out her (fiction and nonfiction) books at TKThorne.com

T.K. Thorne writes about what moves her, following a flight path of curiosity, reflection, and imagination. Check out her (fiction and nonfiction) books at TKThorne.com

When I was young, I had a deep need to understand the meaning of life. It consumed me. A knot inside that HAD to be untangled. Why was I alive? Why was I me?

I believed if I thought about it hard enough, I would figure it out. (Hubris, that!) I knew the answer was out there somewhere.

Adults did not seem particularly concerned about the meaning of life. How crazy was that? What could be more important? But one idea scared me more than realizing that everyone wasn’t going around absorbed by this great mystery—the fear that when I grew up, I would be like them. In my diary, I wrote my adult self a stern message, admonishing her/me against settling for complaisant acceptance.

I read a lot in this quest. Alan Watts was a great inspiration and guide, giving me difficult concepts to chew on, such as the mind being like an onion—you peel layer after layer, thinking you are getting to the core, only to find there is no core, only more layers until there is . . . nothing.

I hated that. There had to be a core, a “me.” And there had to be a meaning, despite Watt’s cryptic conclusion, “This is it.”

Many people follow an ideology that journalist Derek Thompson calls “workism,” a belief that work provides one’s sense of identity and purpose. As a former police person, I get it. You put on more than clothes with a uniform; you put on an identify. Retiring, many are unable to find a center to hold onto when that layer peels off. What happens when children go off to live their own life? When a parent dies? A spouse?

Who am I, if I am not a [cop, nurse, entrepreneur, doctor, builder, artist, spouse, parent, friend, etc.]?

I thought I had escaped that trap in my retirement because even during my law enforcement career and the one that followed, I knew my real and true self was not that work (although I did it wholeheartedly).

You see, I was a writer. All this other stuff was what I did, but not who I was.

And then I retired. I still wrote, but I wasn’t as consumed with it as I had been. How could that be if that was my true self and life’s purpose?

I was free now to pursue my art on my own terms. But strangely, other things started to take my attention, things I found I loved too. This surprised me. It challenged my perception of myself.

Who was I now? I was still determined to find out, because the answer to that question seemed entwined with the meaning of life. We need to be who we truly are. Right?

I did a lot of things. I redefined myself as an artist, a martial artist, a teacher, a very humble gardener.

But I knew I was none of these things . . . or I was all of them.

Elusive, this meaning-of-life thing. Is it an onion, after all? Are the peels just what we do?

What if I die without finding it?

What if I get old and stop doing?

In my mind, I jump ahead:

I am old. I am still. I look out on my garden and the stack of books I have written, the paintings I have painted. Remember the children I have taught. My friends are gone. Family gone, except for the young who are living their own lives.

Old. Forgotten. Maybe I am in a place where they put old people who stop doing. Now what? Who am I? Are only memories left? Is that why old people are still?

What was my life about? Did it mean anything? Am I worthy of it if I just sit here?

Wait.

Is it possible that there is no one-size-fits-all? That the meaning of life is not the things we do, not the breakthrough understanding, not something we find at all, but something we . . .

create?

Well then.

Maybe I will create a meaning right here in this moment, a meaning to breathing in and breathing out. A meaning to smiling at the cranky woman on a walker who hogs the hallway every morning. A meaning to inhaling the turned earth of the rose bed outside my window or the taste of fresh-from-the-oven bread. Maybe just remembering. What is writing at all but remembering? In the moment we pen, the moment we write about has already passed.

So maybe I will scratch out a few words with my arthritic, age-splotched hands, words on a napkin bound for the trash bin. Or maybe words that might touch another someday, a fellow human seeker looking for who they are and . . .

the meaning of life.

T.K. writes about what moves her, following a flight path of curiosity, reflection, and imagination. Read more about her at TKThorne.com.